Melody and rhythm are almost inextricably linked. I say ‘almost’ because you can have melody or harmony without a distinguishable rhythm, and rhythm itself can exist with no melodic content at all. The examples here contain elements of both, but I wanted to draw a clear distinction between the two before we start.

Many songs can be recognised by hearing the rhythm alone. Artists such as Bo Diddley can even make a rhythm their musical signature, while Steve Lukather has created memorable rhythmic parts that really push a song along using a single note!

I’ve leaned towards a funk style for these examples – this makes it easier to focus on the rhythmic element – but the kind of funk I’m referencing is ‘old-school’ R&B/Motown. Think Earth, Wind & Fire, The Spinners or even Band of Gypsys-era Jimi Hendrix.

Having made that point, let’s get back to a more traditional blues standpoint and consider players such as BB King, Albert Collins or Eric Clapton. Would you agree that their choice of rhythm is as integral to their style as the notes?

Of course, it’s one thing to acknowledge the importance of rhythm in guitar playing and another to set about methodically improving our practical skills in this area. And that’s where the examples come in.

If you divide each beat of each bar into four, then play any note or chord using alternating downstrokes and upstrokes, you’ll find yourself playing the classic funk ‘16 to the bar’ rhythm – think Nile Rodgers.

The skill is in choosing which notes to emphasise, or maybe skip entirely, while maintaining the alternate strokes (even if the pick doesn’t contact the strings). There’s no need to hit the strings hard unless you’re going for a specific effect (see Example 2). See you next time!

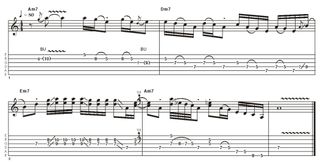

Example 1

There are a few things going on here. First, this is mostly palm-muted. Second, in spite of this there are shorter and longer notes, hence the staccato markings.

Third, though the underlying pattern is alternate-picked 16th notes, some are accented, some muted and some omitted completely, all while preserving the sequence of downstrokes and upstrokes.

Last but not least, keep it relaxed: if anything, pull very slightly back, rather than pulling ahead of the beat. A funk song might just use two notes, but I’ve gone a bit more bluesy and pentatonic!

Example 2

I’m attacking the strings more aggressively here, which gives a harder ‘pingier’ sound. I’m muting unwanted strings with my fretting hand, rather than the palm of my picking hand, which gives this example a different character from Example 1.

I’ve taken a few more liberties rhythmically, culminating in a more ‘lead guitar’-style doublestop phrase to finish. Hopefully, this starts to hint at how you might employ this approach in other scenarios, particularly a bluesy context.

Example 3

Moving further into blues solo territory, this example stays with the same A minor pentatonic position as Examples 1 and 2.

There is less emphasis on keeping a constant rhythm with alternating down- and upstrokes, but you should be able to see how the rudiments laid out in the first two examples are being put to use. I rolled back the guitar’s tone control a little to smooth the attack for this, though adding a touch of drive could also be nice.

Example 4

This Motown-style rhythm part is another way you might use the alternate ‘16s’ rhythm discussed earlier. This is influenced very much by the kind of playing you’ll hear on The Spinners’ It’s A ShameMarvin Gaye's What’s Going Onand Earth, Wind & Fire’s That’s The Way Of The World.

It’s important to keep the strumming gentle and without too many grace notes. Don’t let it get too ‘choppy’ or aggressive, either. That can have its place, but shouldn’t be the default.

Hear it here

James Gang Rides Again – James Gang

Joe Walsh is great at combining funky rhythms with blues-rock riffs and pentatonic lines. Check out Funk #49, Asshtonpark and Thanks (though, really, this is one of those albums you should play all the way through).

Throughout, Joe manages to sound bluesy and rocky, with hardly a traditional powerchord to be heard. Note also how certain chord inversions are employed to allow a seamless transition into pentatonic lines – and back again!

Fire and Water – Free

Free’s music has always had a great rhythmic feel, with well-arranged complementary guitar bass and drum parts. Once you’ve played through the examples, take another listen to how these elements interact on the title track, Oh I Wept and Mr Big.

Admittedly, the link between the examples and these isn’t immediately obvious, but without doubt it is the awareness of rhythm and accents that sets this apart from ‘regular’ blues and rock.

A Night On The Sunset Strip (Live) – Eric Gales

Eric Gales is a great example of a modern blues player who has assimilated funk, jazz, blues and heavy rock. Have a listen to Make It There, Sea Of Bad Blood and Swampand you’ll hear the techniques from the examples in action.

As with any technique, you’ll develop a feel for where and how much you use it. Borrowing from great players such as Eric is a great place to start your own rhythmic journey.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings